Can we explain to Artificial Intelligence who we are?

- Caroline Leroux

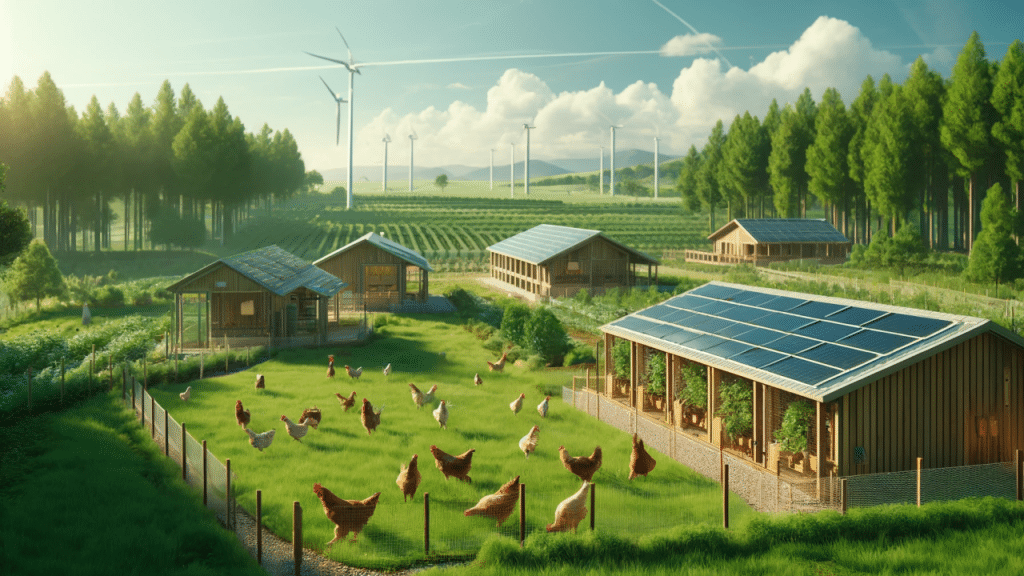

Have you ever tried to ask ChatGPT or another AI chat bot to create an image of how a sustainable chicken farm should look like?

If the answer is no, I suggest you do. The result is certainly interesting, but you might not like it.

This is how a “sustainable chicken farm” is represented by Artificial Intelligence, and what it thinks of biosecurity, animal safety, logistical and production efficiency and, consequently, food security.

It is superfluous to go into details about why this representation is not only incorrect, but would also expose animals, production and the entire supply chain to countless risks. However, I believe it is important to analyse why an “unbiased” tool provides a picture so far from the truth.

Regardless of the ethical judgment on Artificial Intelligence, this technology will revolutionize our world, for good or bad, in ways that we cannot yet imagine, not only by providing awesome tools and opportunities, but also by posing a serious dilemma regarding the “legacy” that human activities will leave for future generations.

Despite the name “Intelligence”, these technologies today collect all the relevant information regarding the given question and assemble it, creating a content that expresses the majority of what they were able to retrieve. This exercise is extremely useful but contains an intrinsic problem, how reliable are the starting data from a qualitative and quantitative POV?

Rubbish In, Rubbish Out has always been a problem when building systems. Think of the challenges encountered in a basic data collection: the definition of metrics, what to measure, how to measure it and what to report. It is amplified exponentially both by the lack of control over the “data” selection process and by this tool simply accessing what’s available regardless of its validity.

In a previous article, I explored the topic of taking back control of communication and narrative about the poultry meat sector. The use of Artificial Intelligence for communication purposes amplifies and brings this debate to a higher and more delicate level. In fact, we cannot ignore that nowadays it is not only the quality of the information that our sector makes available to the public that counts, whatever it is, but unfortunately its quantity also counts. Obviously, the second must not be pursued at the expense of the first, but it is vitally important not to fall behind in terms of critical mass.

Detractors of livestock farming, or of the poultry sector in particular, have an easier time on this. In fact, when you simply have to criticize without dwelling on the scientific bases and trade-offs of what you say, your message will easily be similar, regardless of whether it comes from one country or another, generating a huge and aligned mass of information.

On our side communication is combined with other activities, with production as the main one, and this split focus puts at risk both the quality and quantity of correct information that we can make available.

The good news is that we are increasingly witnessing shared initiatives, unity of purpose and pre-competitive communication by those who actually produce, as well as by the scientific community.

Companies and associations of producers are increasingly vertically approaching communication, including all the actors of the value chain, with globally shared messages and building a comprehensive narrative without necessarily responding only to a specific criticism.

We are the ones who must establish what the “legacy” of our sector will be, how we should be perceived by Artificial Intelligence, and this will necessarily pass both through the quality and quantity of correct and shared information that we will be able to produce.